Education & History

A New Chapter in Lancaster’s History

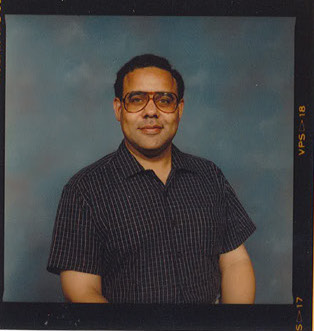

Dr. Leroy Hopkins is a local historian, Millersville University professor emeritus of German, and Lancaster resident. He received his bachelor’s degree from Millersville and his Ph.D. at Harvard University.

Dr. Leroy Hopkins is a local historian, Millersville University professor emeritus of German, and Lancaster resident. He received his bachelor’s degree from Millersville and his Ph.D. at Harvard University.

Over the last 40 years, Professor Hopkins has been collecting, researching, and writing about Lancaster’s African American history. He has published nine articles in The Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society. He has stepped down from his role as president of the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania to do extensive research for his latest passion project: a documentary on African Americans’ history in Lancaster county.

Dr. Hopkins has had a fascinating life with a unique perspective on what it is like to grow up as a black man in Southeast Lancaster City and beyond.

When many people think of Lancaster City, they think of a quaint little city in the middle of Pennsylvania Dutch country. If they grew up within 50 miles of Route 30, they probably think of the outlets, the smorgasbords, and family-friendly entertainment to be found at the local theatres. They might not consider the African American contribution to the culture and history of the city we see today. Dr. Leroy Hopkins, Lancaster resident and local historian traced his African American ancestry back to the 1700s. Now he is devoting his time to telling the stories left out of the history books.

One of the best parts about speaking with Professor Hopkins is the lack of pretension in his manner. The retired German Professor and former President of the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania can quote a famous British historian and a nursery rhyme in the same conversation. He is an intellectual with an expansive vocabulary, which one would expect from a retired language professor, but he also has a dry wit and engaging demeanor that invites conversation.

Professor Hopkins was born in 1942 in what is now Lancaster’s Southeast, and his memory is firmly rooted in geography. Although he has pleasant recollections of walking familiar streets, buying penny candy, going to work, or seeing old flicks at the Hamilton, he also has memories of the places he couldn’t go. “I was aware that for me there were two areas: ‘The Ward’ and ‘The Hill’… ‘The Hill’ was forbidden territory for people who looked like me… From its inception until well into my early adult life, Lancaster [was] a segregated society.”

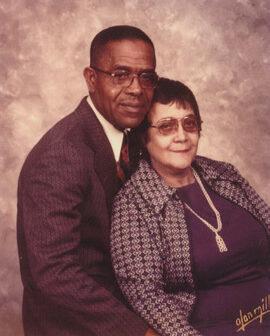

Leroy’s Parents, Taft Hopkins and Mary Ella Peaco Hopkins

When asked about his experiences as a young man facing personal injustices because of his race, Professor Hopkins said that he was “caught between lessons” learned from his parents. “My father…endured the daily slights and indignities with which many African Americans encountered without complaint. My mother, on the other hand, was a firebrand and, being just 4’11,” stood tall for her rights.” He tells a story in which a clerk at the local Five and Dime tried to serve a white customer behind her in line, and his mother bravely stated, “Hey! I am next. My money is just as good as theirs.” That was unheard of in those years. “I did not have my mother’s courage [then], but I have acquired a modicum of it over time.” That courage has manifested in his fight for access to African American History in his community.

“I did not have my mother’s courage [then], but I have acquired a modicum of it over time.”

Like many African Americans, including those in the Civil Rights Movement, Professor Hopkins’ community involvement began in the Black church. His family attended Bethel A.M.E. Church. Its pastor and its members had a vital role in shaping his early years. When he was 17 years old, Mrs. Betty Tompkins, who was also a member of the Lancaster chapter of the NAACP, organized a trip to hear Martin Luther King Jr. speak at a church in Philadelphia. A few years later, his Sunday School teacher Mrs. Hazel Jackson took him to a PACE (Program for American Cultural Enrichment) meeting. Those meetings began filling in the gaps that traditional schools left out of their history lessons. “In school, l had learned nothing about my heritage except that slavery existed, it was abolished, and George Washington Carver did marvelous things with a peanut.”